In this post we’re going to take a look at one of the residential typologies we experienced in Denmark, the Perimeter Block. They are fairly common in many northern European capitals, and we’ve seen something similar in places like Sweden and Germany. They are the foundational residential architecture of Copenhagen and typify the city more than any other city.

One of the first things one notices in Copenhagen is the rather large, uniform blocks in many central neighborhoods. Above is park in Vesterbro, which is mostly late 19th and early 20th century construction. Here is the same area, viewed from above:

As you can see, what looks like a massive, solid block from the street is actually quite a slender structure with a large void in the center. From front to back, these buildings are typically about 36 feet thick or less. This creates a large central courtyard which enjoys ample air and light.

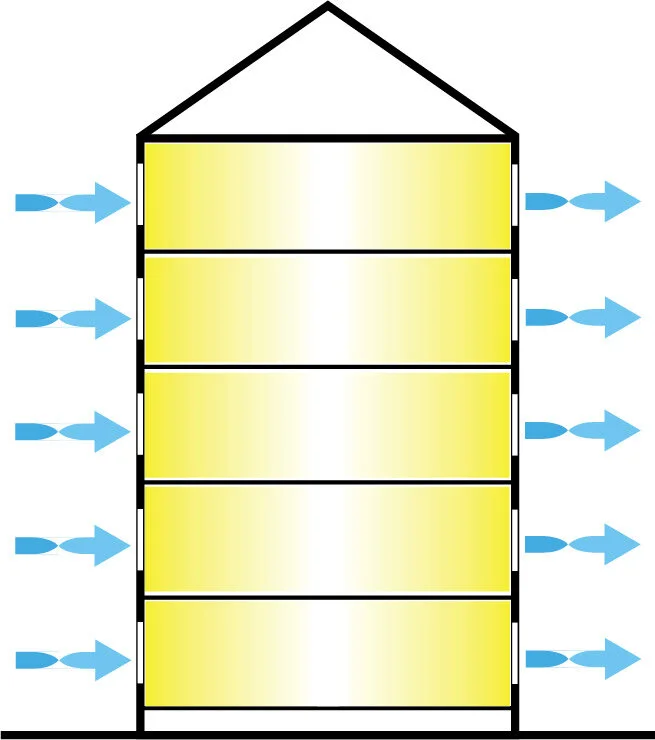

The reason the buildings lining the courtyard are so thin is that they are only one unit deep. That means that each unit has two window-walls, one facing the street and the other facing inward to the courtyard.

This configuration is possible because instead of a single entry and a central corridor, these units are in stacks that share a central staircase. Each “front door” typically serves no more than 10 families.

Often a second back stair provides access from kitchens to the courtyard side of the building. The generous size and shape of units makes them ideal for families. Most importantly, the through-building format of the stacked units allows them to function like a house in terms of daylight and cross-ventilation.

While the outsides of the blocks can seem at times hard and dreary, the interiors are a green oasis.

The central courtyard creates places for children to play outside their apartments in safety. They also allow for gardening, bike sheds and general relaxation for the residents of the block, who essentially share their own private park.

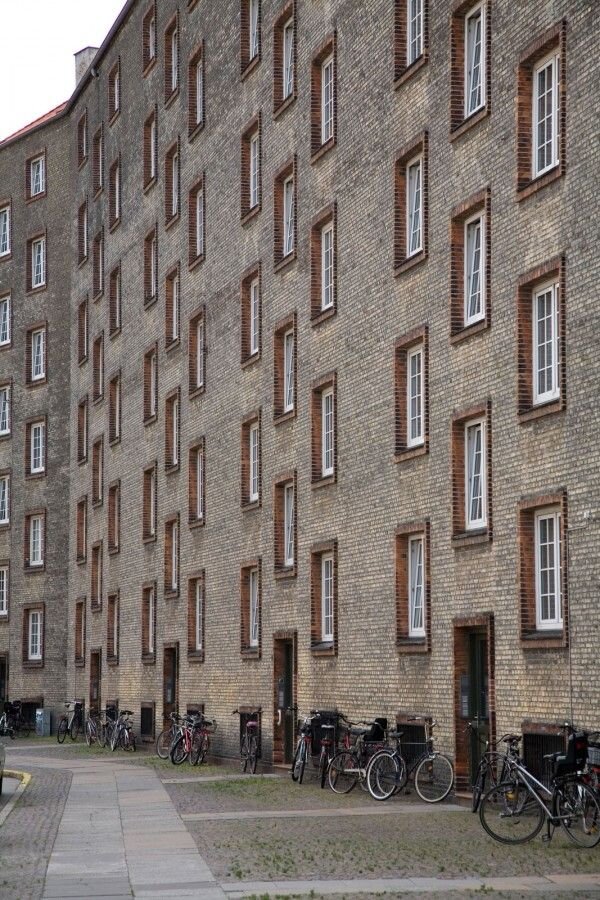

The biggest downside of the perimeter block is that in some cases, they can be monotonous and grim from the outside.

In older neighborhoods, the perimeter building was not a single building, but a series of segments joined together to create a perimeter block. The inherent variety livens things up. Different colors, materials, and often, even different floor heights provide variety. Buildings of different ages and conditions foster diversity.

Better designed blocks eliminate this by creating detail appropriate to the scale of the building. Note the “rule of thirds” hierarchy, where every element is approximately one third the scale of the larger element it is nested within.

The perimeter block is alive and well today. We found some very exciting examples in the new urban Sluseholmen neighborhood in the Sydenhavn district. Built on former industrial docklands, the area’s perimeter blocks are bounded not only by streets, but a network of canals.

By contrast, the typical American apartment building format provides a primary entry and access to units via a central corridor, like a hotel. There is an advantage of efficiency, since a few stairs and elevators can serve an entire building. However, the building itself becomes much thicker from front to back and most units end up having only one outside-facing wall

In a typical pre-war apartment building, unit width was greater than depth in order to maximize daylight. In environmental design, the area of a room that is considered “daylit” is defined as the height of the top sill of the window x 2. So if the top of the window is 7 feet off the floor, then 14 feet inboard of the window is daylit.

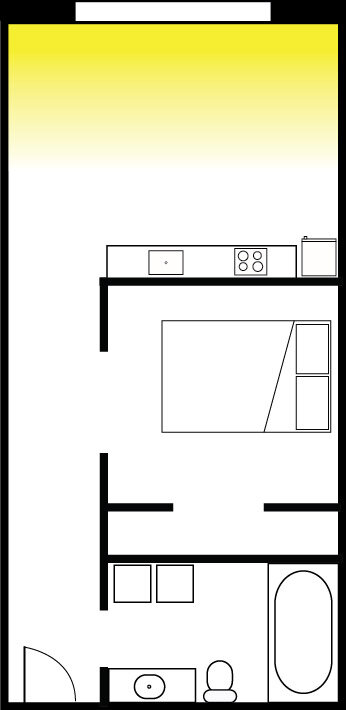

If this situation had some drawbacks, the status quo in the industry today is exponentially worse. In recent years (perhaps 2 decades or so), large developers realized that they could maximize leasable space by turning the units sideways so that the short end faced the outside. This resulted in the default configuration of contemporary urban apartments; long narrow units with daylight at the “end of the tunnel.” This configuration maximizes efficiency and generates the most bang-for-the-buck for investors.

This is accomplished by making a bedroom that is not quite a legally-defined room, and therefore needs no window, and eliminating the kitchen as a separate room, moving it onto a wall in the living room. As a result, we end up with a long dark unit. This type of building is really only suitable for small households. To the best of our knowledge, this double-loaded hallway building configuration is not allowed for apartment buildings in Denmark.

The double-loaded central hallway configuration can pack up to140 units per acre, compared to the typical Danish courtyard building which averages 60-70 units per net acre. That’s a lot lower, but for comparison, a typical single family block in Portland has a density of about 9 units per net acre.

Very large American apartment buildings like this one proposed for SE Belmont fill whole blocks, but unlike their Danish counterparts, they maximize the economic output of the building system while providing a unit type that is not very adaptable. We’d argue that while the American system is good for investors, and helps cities achieve short-term goals of reducing the shortage of dwelling units generally, the type and usability of these units is probably less valuable for the long-term stability and sustainability of an urban neighborhood.