The most basic building block of neighborhoods is the lot. These were established when the city was first platted.

In this section of the PDX blog, we’re going to examine the building blocks of urban neighborhoods. This will allow us to articulate what makes neighborhoods great and develop tools and practices that build on this knowledge base. Let’s begin with an exploration of the nested hierarchies that create the sense of scale that allows us to understand how we, with our human bodies, relate to our built environment.

In pre-WWII urban neighborhoods, you can find an easily legible nested hierarchy in the way space is divided. We encounter neighborhoods, which are made up of blocks with a grid (or something approximating one) carving up private land at fairly regular intervals. The blocks or private areas between the streets, are broken in to lots, and sited upon each lot is a building.

Here we see a page from the 1905 Baist’s Real Estate Atlas of Seattle. Similar patterns prevailed in most North American cities.

Here is the same approximate area today… and below, an area of similar vintage in Portland.

In Portland (and most cities that grew during the same era), the standard lot was 50’ x 100’. This is the basic unit of urban form. Sometimes these were subdivided, and in some cases, consolidated to form larger lots.

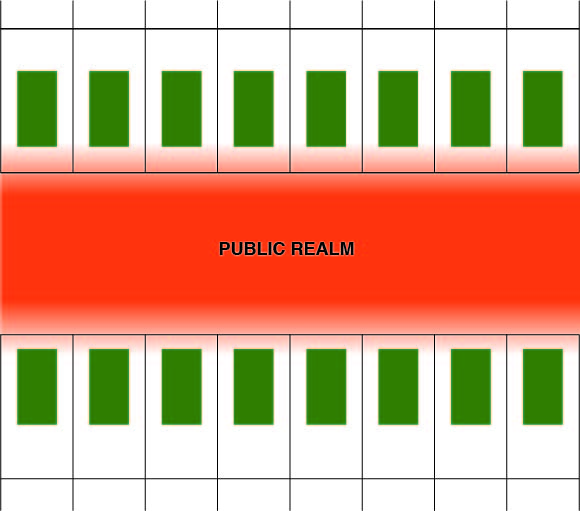

In a typical condition, these lots are oriented on a block with the short end facing the street/public right of way, and the side abutting similar lots. To borrow a biological metaphor, we can consider the short ends the end grain, and the long sides the side grain, as in wood and lumber. Put together these form a block of a fixed width (two lot depths wide, typically 200’) and an arbitrary length, depending on how many lots were assigned per block in the plat.

This orientation is the most efficient way to arrange lots, as it maximizes the number of lot frontages on a given block. Meanwhile, the fronts of buildings oriented to the street, the city’s most commonly occurring form of public open space. Streets provide the public world (what urban designers like to call “urban rooms”) that provides the setting for all the coming and going of life in these neighborhoods.

In subsequent posts, we will revisit these hierarchies and their implications for how we design our homes and how we use our public spaces.