Photo by u/pnwmommy on Reddit

We decided to take a look at a possible future, for Portland’s perpetually undead Dead Mall, the Lloyd Center. A lot of proposals have been put forward, some serious, some silly. It’s our frank assesment that the mall itself has outlived its useful lifespan, and the opportunity cost of trying to repurpose the structure is just too high. What we mean is, it could be adapted for some other use, but by doing so, we foreclose all the other possibilities that arise from demolishing it, and the missed opportunity is worth more than any efficiency from keeping the carcass on life support for another generation. You know the phrase, ‘leaving money on the table,’ in reference to a deal where you don’t get all you could for something. Well, in this case, the ‘money’ is housing where it’s needed most, and a great urban neighborhood, where there’s underused relic of mid 20th century car culture and consumerism.

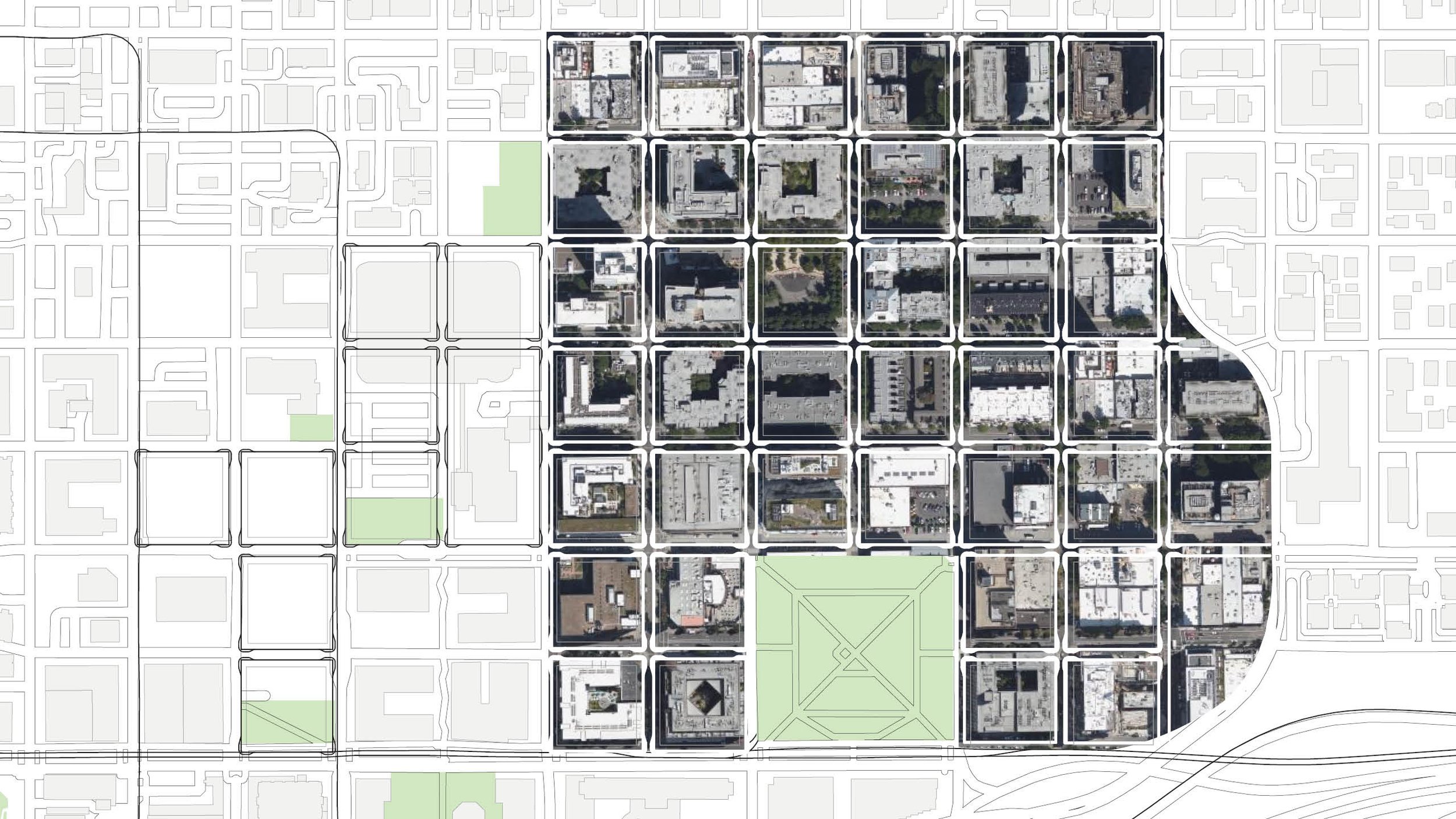

Existing mall and vicinity

We didn’t come up with any wild ideas here, or even particularly exciting ones. This is a sort of baseline capacity study, to see what, at a minimum, could be achieved if the city grid grew back where it once was, and the blocks filled in with midrise development appropriate for a central city location adjacent to downtown and high capacity transit.

Here’s the existing development pattern. Note how out of scale the footprints are with the surrounding urban neighborhood. This is big pixel, low resolution urbanism.

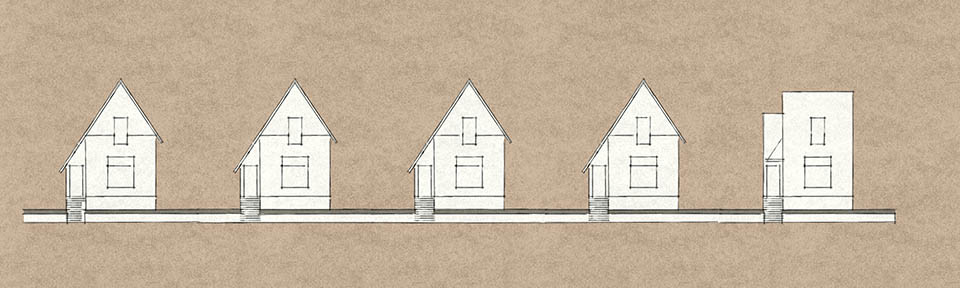

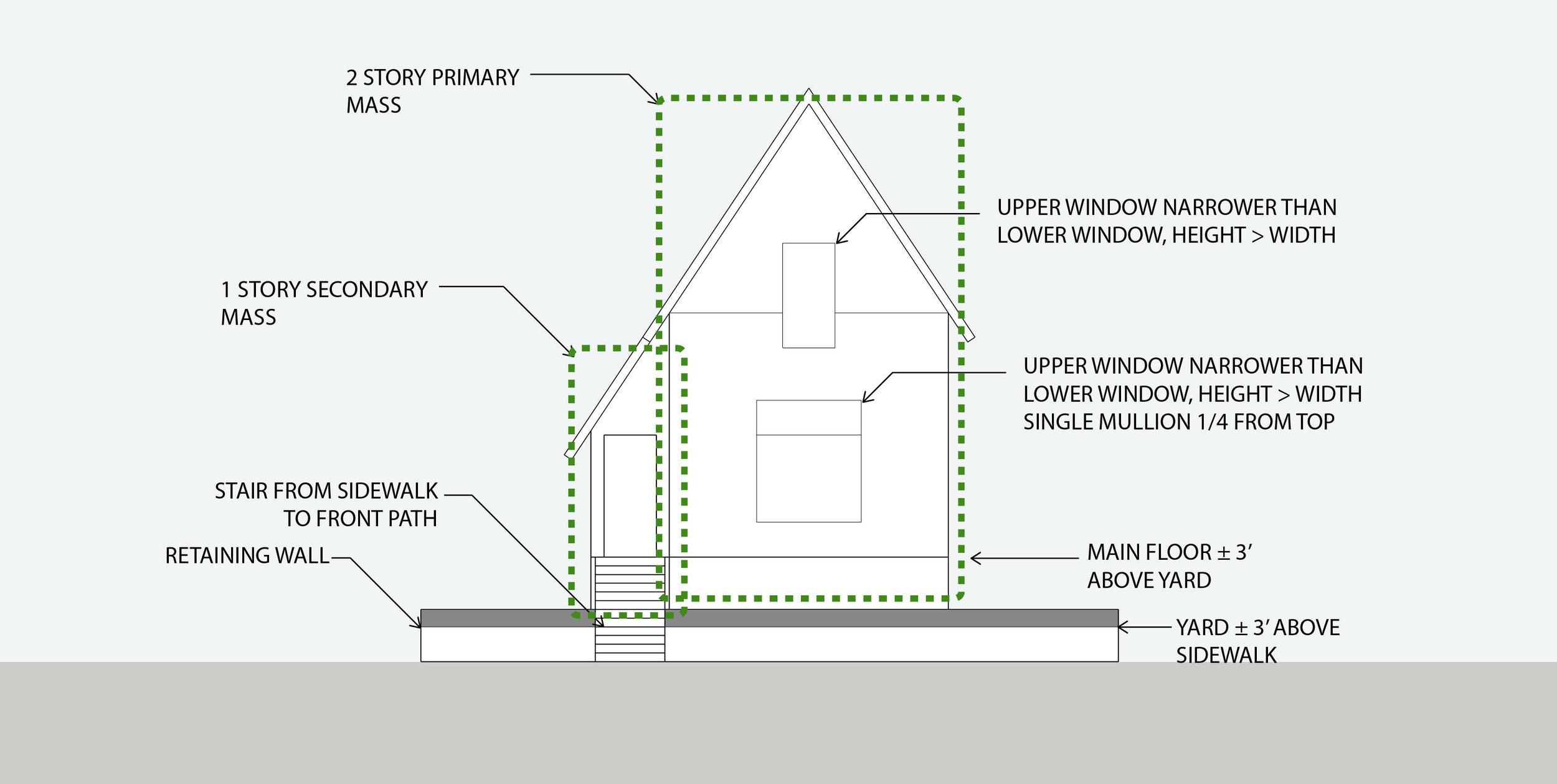

But if the street grid were to heal over the wound, there’d be some major opportunities for a granular, walkable neighborhood to grow.

Finally, we grabbed an aerial of the equivalent number of blocks from the Pearl and dropped them in. The shift in scale is stunning.

These blocks, representing the core of the mall and its immediate vicinity could make a significant dent in our housing shortfall. If the area were to follow the development pattern of the Pearl District, averaging around 200 dwelling units per acre, it could easily accomodate 7,000 new apartments, and become home to somewhere upwards of 11,000 people! If the pattern were extended west towards I-5 those numbers could be doubled, and all this could be accomplished without the sacrifice of any historic buildings or residential displacement (the handful of existing apartments near Broadway and Weidler would not need to go).