This week we’d like to introduce the concept of the urban Transect as a way to understand the taxonomy of our built environment. The term emerged from the New Urbanist movement a couple of decades ago as a way to talk about the different concentric layers in the structure of a city. The term is borrowed from biology, where the transect was used to describe the various distinct zones form shore to inland forest.

(Source CNU)

The transect methodology shows that different areas of the city can be classified by the scale of buildings they contain and the intensity of uses located there. New Urbanism’s transect runs the gamut from farm and forest, through the suburbs and into the urban core. It even sets up a special category for “special purpose districts.”

(source: CNU)

Let’s take a look at what a transect is and how it works. A journey from the center of Portland, through its suburbs, through its rural hinterlands to the wilderness reveals the astute nature of the New Urbanist’s observations. We travel from the corporate towers of the Central Business District (CBD) through the rapidly developing mid rise areas like the inner east side, to the street car commercial districts and early 20th century neighborhoods, with their modest houses packed together on small urban lots. Eventually the pre-war streetcar city gives way to the inner ring post-war suburbs with their auto based patterns. These are places like East Portland, on the far side of I205, Cedar Hills, Raleigh Hills, Milwaukie and Maywood Park. Eventually we reach the later suburbs, where a more relentless auto based morphology asserts itself, replete with corporate chains in near identical strip centers and large scale housing tracts developed by corporate developers. Finally, we clear the Urban Growth Boundary and enter the orchards, tree farms and vineyards in places like Corbett, Sauvie Island, Banks and Boring. Since we’re fortunate to enough to live in Oregon, our transect reaches to relatively pristine wilderness in our National Forests.

CNU/Plan Design Xplore

We think the transect is a great way to look at Portland’s urban fabric. We’d like to posit that the various housing typologies we’re documenting with our case studies have ideal habitats, and that those habitats can be described by transect zones and sub-zones.

In the ideal-typical model of a city, as conceived by the New Urbanist transect, is basically a series of concentric rings. Viewed in three dimensions, it’s a tiered wedding cake of density and intensity, with the CBD at the center. In reality a transect map of most cities, Portland included, would be more irregular. It would appear as more of an octopus, with tentacles spreading outward from the core.

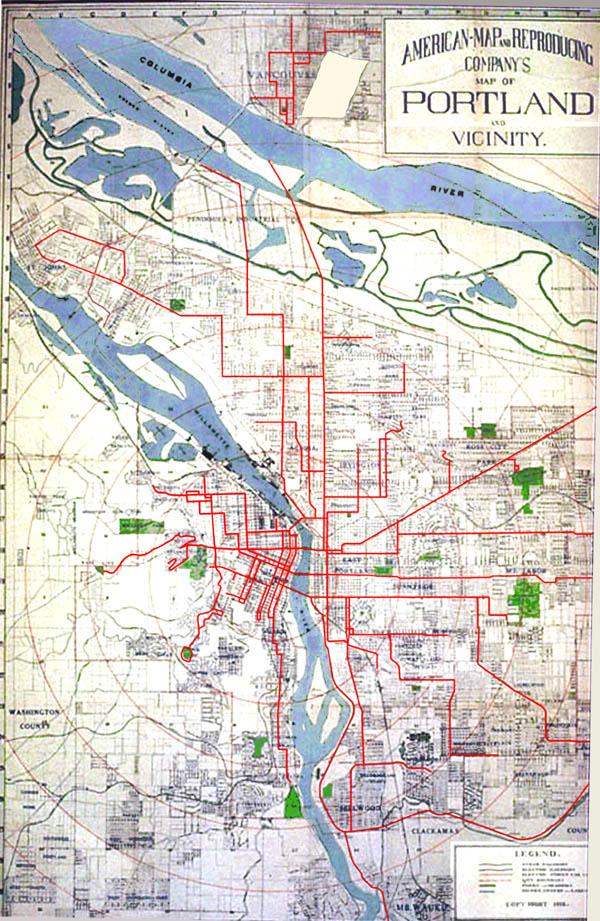

This distribution reflects the way the city grew in its first century, starting at the core and spreading out along streetcar lines. In its spatial form, Portland is a classic “street car city.” Most of our fabric (note this only applies to Portland proper, and not the suburbs and exurbs that later merged to form today’s metropolis) was platted and developed before WWII.

Our distribution of houses and business corridors reflect a pattern where workers commuted via streetcar to the core. In the evening, they’d return home on the streetcar, and get off at the cross street where they lived, stopping to make purchases as they disembarked. For this reason, our arterials, most of which are former streetcar lines, are lined with what is referred to as “street car commercial buildings.

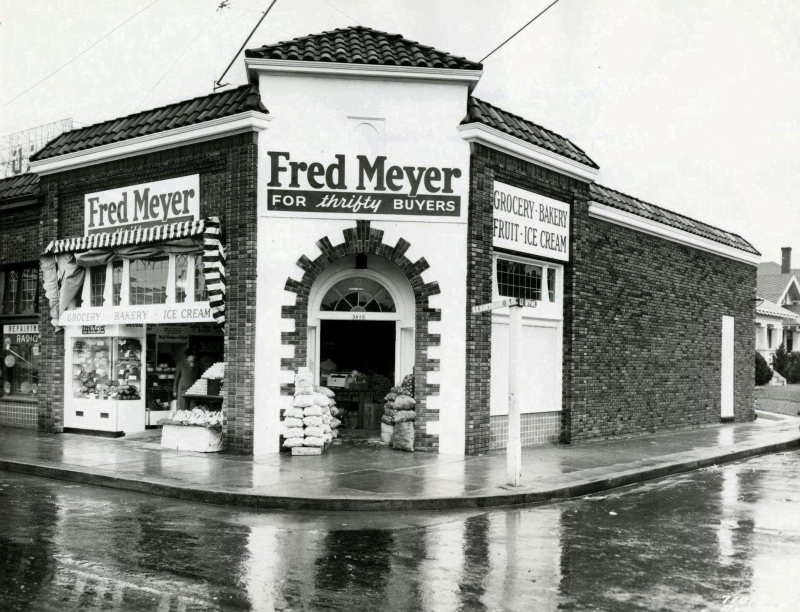

The original Fred Meyer, at SE 36th and Hawthorne. Now home to Bread & Ink Cafe.

The commuter would then walk back to his house with an arm full of provisions from Fred Meyer or whatever local merchants lined his commute, to his house. This resulted in a pattern of streetcar lines at intervals, and houses in between. Density ramps down as one moves away from the arterial, then back up again approaching the next arterial.

If we’re going to apply this logic to Portland in a meaningful way, we will need to parse the transect zones a little more finely. We propose adding a second tier to the hierarchy for urban zones. This yields a sequence of T3, T3.5, T4, T4.5, etc.

Our new Portland specific transect hierarchy could look something like this:

T3 = East Portland

T3.5 = Inner neighborhood residential areas between boulevards.

T4 = Streetcar commercial corridors

T4.5 = Primary arterials

We’ll dive deeper into this Portland-specific transect hierarchy in a future post, as it’s a topic deserving of some serious research, especially if we want to use it as the basis of policy recommendations.

As an aside, we will probably want to consider suburban transects in tandem as we plan and manage our growth. Portland and its suburbs are managed by a regional plan, the Metro 2040 plan, which was conceived as a holistic regional growth management plan. To our knowledge, Portland is the only metro in the US with a regional plan that has any real teeth - other cities claim similar but they are merely aspirational documents, not policies. Meanwhile, even within Portland’s city limits, there’s quite a bit of post-war suburbia. Beginning in 1981 Portland annexed East Portland, which had hitherto been the no-man’s land between Portland and Gresham. This area of small farms and orchards urbanized in a piecemeal fashion in the decades immediately following the war and lacks much of the infrastructure or formal coherence of the city west of I-205.

The appeal of the transect is that it is intuitive and familiar - we get it, whether we’ve known a name for it or not. Indeed, the concept is has been around for a very long time and not just in the West even:

And like David Byrne, we’ve all observed it as we make our final approach, our seatbacks upright, our tray tables stowed, and all electronic devices switched off.