On a chilly Saturday in February a couple dozen neighbors gathered for a hypothetical experiment in community-led planning, under the auspices of a project called Dynamic Density, created by the team from ReUrbanist Collaborative - architect Rick Potestio and urban designer Jonathan Konkol (me).

What is Dynamic Density?

Dynamic Density was conceived as a tool for neighborhoods to use to allocate new housing in a context-sensitive way that benefits the community and offers a degree of control over the design of buildings. We have observed that many of Portland’s densest, and most desirable neighborhoods are a jumbled up mixture of single family houses, large buildings, and everything in between. Examples of this are Kings Hill, where Rick lives, the southern half of Irvington, where I live, and other places like Sullivan’s Gulch, Buckman, the Alphabet District, and others. These places took shape before modern zoning was established.

Under our system, neighborhoods would assess the existing blocks and buildings in their community and decide what buildings, trees, businesses etc. are extremely valuable to residents, and should be off-limits to demolition and redevelopment. The second part asks neighborhoods to find places for a specified number of new homes - each community’s share of anticipated growth - by allocating building types on the remaining properties. In order to ensure compatibility of the new housing with the existing neighborhood context, we provide a menu of pre-WWII multifamily buildings we have compiled from walking Portland neighborhoods with our cameras and tape measures.

Why do we need to do this?

As most people are aware, Portland, like all west coast cities, suffers from an acute housing shortage, which has driven the cost of renting or buying a home out of reach of many people. As construction has not kept up with a growing population, people forced out of the housing market have ended up on the streets, creating a crisis that threatens livability for everyone.

Meanwhile, Portland, once a success story for progressive planning, has been unable, or unwilling to do the hard work of planning how it will grow in the last couple decades, and now we’re dealing with the consequences. We have pushed new housing construction out to the edge of our urban growth boundary, into places that are nearly impossible to serve efficiently with transit, and congestion has consequently become an ever increasing problem. The governor and legislature have responded with blunt instruments that may have some short term benefits, but I believe, are profoundly short sighted and destructive; attempts to override our urban growth boundaries, and lifting development restrictions on existing neighborhoods without any attempt to preserve the qualities that made people want to live there in the first place.

To be clear, the city as a whole is very low density and should accommodate many new, larger buildings. However, the planners’ approach does not address architecture or preservation at all, perhaps because it’s just too much work! We can do both, but it requires more sophisticated tools than our government is using. Dynamic Density is the tool we’ve developed to solve this problem.

Speaking strictly for my own motivations, I have put countless hours into this project over the past five years out of a desire to find the best way to balance the competing imperatives to expand the amount of housing while sacrificing as few historic buildings as possible and without sacrificing the look and feel of our historic neighborhoods. From my experience studying and practicing architecture and planning, almost all NIMBYism is a perfectly natural reaction to the rubbish the architecture profession has generated in my lifetime. There are always good examples to be found, but at a gross level, people are right to be anxious about the quality of design to be expected of a new building, when an old one is knocked down to make way for something new. People, by and large, react to things that look ugly and cheap, and that is what my profession has been pumping out.

What happened at the workshop?

We divided the participants into three groups, all with 600 dwelling units worth of legos. Each group had a somewhat different task thought; each group had a different combination of bricks, representing different types of multifamily buildings.

Team 1 was given mostly small buildings: duplexes, four-plexes and 8-plexes. Team 2 got a selection of medium density building types: four-plexes, eight plexes, brickers and a few L-shapes. The third team got a bag containing several towers, some L-shapes, and a few brickers. In many ways, the low density team had the most difficult task. They had by far the most buildings to find homes for on the map. By contrast, the high density team had far fewer decisions to make, though they may have been difficult ones. With the fewest buildings to place, they didn’t need to worry nearly as much as the other teams about what would have to be demolished to place their 600 units on the map. We also told this team that the lots fronting Broadway are off limits, as we’re anticipating new legislation will likely be aimed squarely at parcels with residential zoning, and Broadway is already zoned for 6-8 stories. In a more rigorous version of this exercise, we’d have placed this restriction on all the teams, but as it turned out most people intuitively understood that it would make no financial sense to place duplexes and fourplexes in locations where most such buildings have already long since given way to more lucrative commercial buildings and apartments, and zoned for more.

Lessons Learned

This was a lesson in trade-offs. The approaches to growth posited by our three team scenarios offer a spectrum of alternatives, and selecting the right one for a given community entails balancing that community’s priorities. One can minimize changes in the scale of buildings - their bulk and height, or, one can minimize demolitions of existing buildings by keeping the footprint of change small and going up. Mathematically, one cannot do both. My personal bias is to preserve as many historic buildings as possible, so I prefer an approach that uses a few tall buildings, placed with some intentionality, to make room for new residents without sacrificing the non-renewable resource of historic buildings. Your preferences may vary, but the Dynamic Density approach offers us the tools to come to the best compromise we can manage, and to do so in an informed, democratic way.

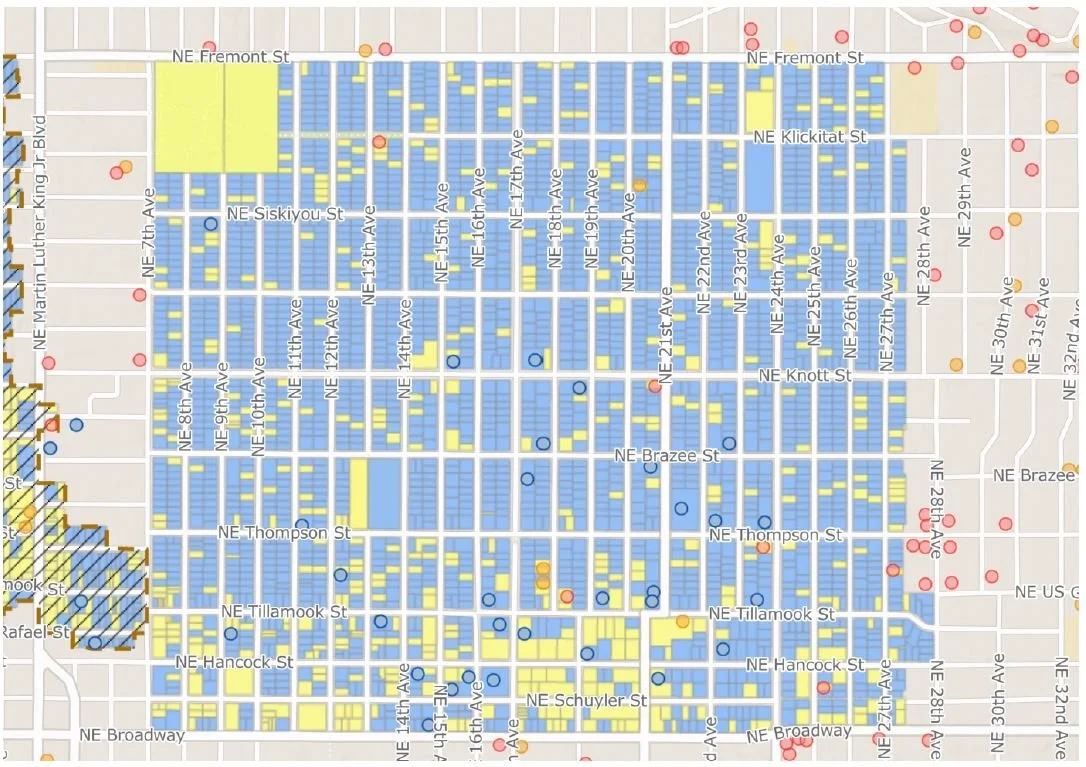

Irvington Historic District: Blue sites are contributing, yellow are non-contributing

The maps we used included color coding for the Irvington Historic District, indicating which buildings were classified as ‘contributing structures’ versus ‘non-contributing’ structures. This made it easy for teams to assess which buildings were of less historic and architectural significance. All teams generally opted to pick the low hanging fruit, preferring to sacrifice non-contributing buildings for denser new buildings to accommodate growth. We think this reflects a basic value most people place on historic buildings that define the fundamental look and feel of a neighborhood. In neighborhoods without such mapping tools already at hand, an exercise like this would likely need begin with teams of people fanning out into the streets with clipboards, and engaging in a process of developing their own list of contributing versus non-contributing structures.

The low density team realized that market economics made their scenario least plausible. The combination of high land costs with low yield per site meant that duplexes and fourplex buildings would have to command very high prices just to break even. Therefore, in a high-value, close-in neighborhood like Irvington, that sort of upzoning would likely result in few new units being added. Moreover, the low density team’s challenge most closely resembles the direction in which state and local legislation is pushing us, and indicating that the current legislative agenda is probably not going to deliver the units promised. With that information, we can surmise that for most communities, some mixture of medium and high-density infill will be the most successful path to realizing our housing targets. This has the added advantage of preserving more existing structures, and limiting the disruption of the urban fabric. The outstanding question is how much height communities are willing to accept, when the alternative is greater numbers of structures demolished and redeveloped.

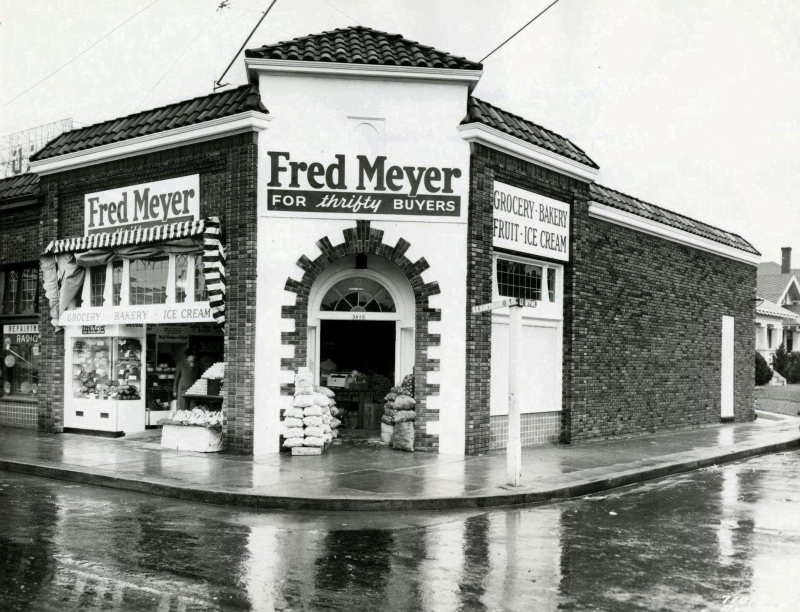

The tour visits existing fourplexes in Irvington

We also noted that there are problems that need to be solved with the way Oregon’s building codes regulate ‘missing middle’ housing. Under Oregon’s version of the International Building Code, any residential building with more than two units must comply with commercial code standards (as opposed to the residential code) which requires costly features like fire sprinklers and greater separation between units. This adds a lot of cost to a fourplex or a sixplex, and that cost is often enough to make smaller historical multifamily building types not financially viable to construct. This will require changes at the state level, and that will have to come from the legislature.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the workshop demonstrated that the stereotype of single family homeowners, and those residing in historic districts, in particular, are knee-jerk NIMBYs who refuse to accept any change and disdain dwellers of multifamily housing is a lazy generalization that doesn’t reflect reality. As one of my mentors has said, “When given good information, communities will always make the right choices.”

In my observation, people generally seem to react with skepticism if not outright fear of new development in their communities because they’ve been conditioned by the bad design my profession has foisted upon them for decades. People love the quality of the architecture and the feel of the streetscape in the neighborhoods where they have chosen to live. They are perfectly happy having neighbors in the pre-auto era multifamily buildings that have existed in Portland neighborhoods for over a century. If we can offer people tools to preserve the architectural heritage of their communities, benefit from growth and have a modicum of control over how it will look, they will make the right choice.

People understood the physical implications of different types of housing and also debated the economic and social aspects. If this were a real-life exercise, I am confident that highly considered and sound decisions would be made. The walking tour was very instructive in pointing out the very different and important characteristics of buildings that in policy terms are identical. The fact that garden court apartments and parking lot apartments can be seen as similar to a bureaucrat, but so different to a neighborhood’s character and social structure is a very significant realization for most people. - Rick Potestio

I went to the meeting hopeful, but not sure that the project would be successful. Sometimes it is nice to be wrong. The people who participated took the matter seriously and thoughtfully, and I thought "Yes indeed, this could work, and for sure it is a better system that the top-down zoning code regulations that are the standard in the United States. - Tony Greiner

The opportunity—and challenge—of density is all in the question of HOW it is done. Proponents of density cite examples of it being done well, and opponents cite examples of it done poorly. When cherry-picking examples, both sides are right—and wrong—and we get nowhere as a community. So, it’s incredibly important to move the matter of density from an abstract question to a specific one. What kind of housing? Where? For whom? How? This is what makes the difference from density being done well versus poorly, and this is what the exercise allowed us to do. Down to the individual plot and unit level we were thinking about how the system could evolve to map to our communities needs in specific, clear ways. It’s the kind of exercise that will help anyone who cares about community development and urban planning, and I’m grateful to Jonathan and Rick for making it happen, and the Irvington Community Association for promoting it, and the wonderful attendees for bringing their full selves to make the session a success. - Caleb Bushner