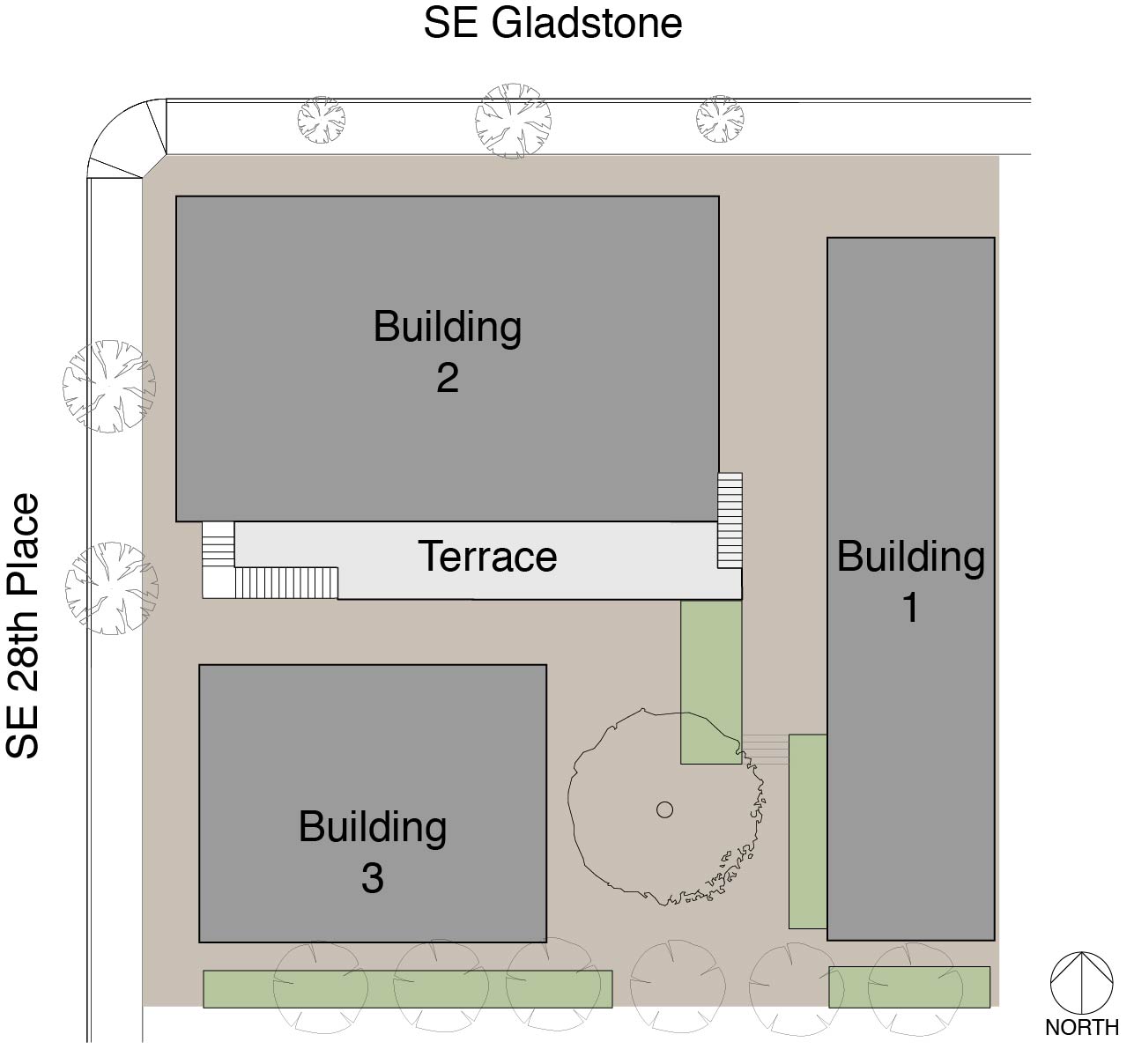

Creston Lofts Building 1 (east)

The following is the second half our Plan Design Xplore's interview, which we began last week, with Architect/Developer Lloyd Russel of San Diego. Our conversation started with a discussion of Russell's Creston Lofts project in Southeast Portland, and lead to a wide ranging discussion of development, zoning and urbanism in Portland.

Plan Design Xplore: What were some of the regulatory challenges and hurdles that you faced?

Lloyd Russell: We didn't have any - I didn't perceive any - I mean the zoning was great and We didn't have problems with that. Our biggest problem was we designed it and Andy had a kid!

And then we decided that can we hold this property for a couple years. We're gonna do something and we got back onto it. The only challenging thing was we had designed it at one point, and then we took it back up again a couple years later just finished - you really raised the money and push it through and stuff like that and the bigger challenge was the financing, I think, because even though Portland didn't require any parking there were a handful of banks that looked at us and said you don't have any parking? We're not gonna give you a construction loan we think you're crazy.

“I think the form based zoning, I mean I love it, but it could be abused, and that’s why the Creston is kind of a critique of that. It’s embracing the form based zoning, but I’m trying to set a model for what I think it should be.”

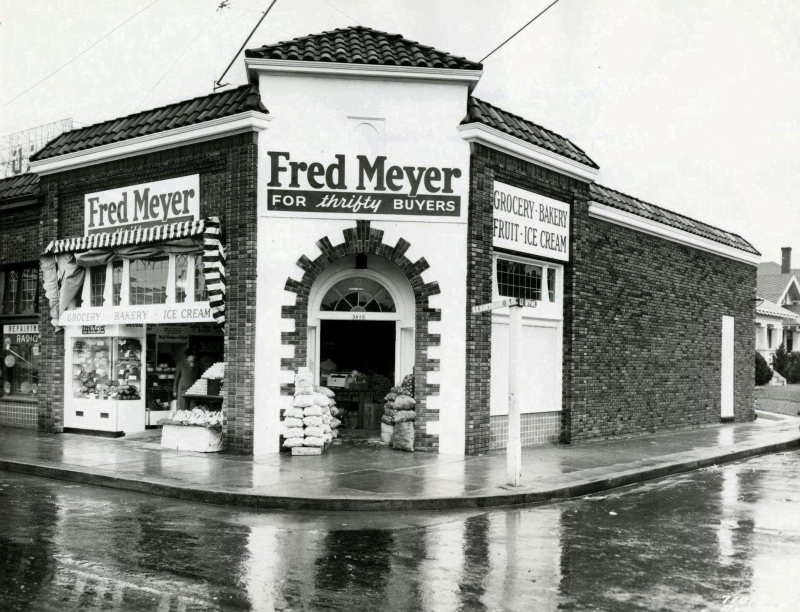

There was also a project on Hawthorne, I think, that exploited that no-parking policy by doing 80 units with no parking, and the Business Improvement District or something had them in a lawsuit or something.

PDX: I think that's probably the one kind near the new Safeway at say about 28th, 27th-ish. That's a large one of the largest projects on Hawthorne.

Hawthorne Twenty Six

LR: That’s one where they’re kind of abusing the zone, and I think the form based zoning, I mean I love it, but it could be abused, and that's why the Creston is kind of a critique of that. It's embracing the form based zoning, but I'm trying to set a model for what I think it should be, as opposed to you know 80 units with no parking and Just maxing everything out that doesn't feel right?

PDX: One of the things that we want to offer is our own critique of development and the development status quo in Portland, and see what are the “black hat” and “white hat” scenarios for development under our existing code and hopefully use form based principles to guide better outcomes.

LR: When we’re teaching, you know you're trying to empower the architect and we talk about… we tell them how to make a pro-forma, how to develop it. How to develop real estate, how it’s very profitable; it's more profitable than being an architect. You know we talked about how these kids can go over to the dark side, and so what we end up with, what we quickly get into discussion about is ethics. What’s the right thing to do?

We talk about it all the time, about housing, and your responsibility in the city and being a good urbanist and all this sort of stuff. I don't think that discussion should ever end. It's not just about maxing out zoning diagrams.

PDX: That's pretty much exactly why we got this project going in the first place is exactly that concern!

LR: Let me give you a little background. So in San Diego, they were building a ballpark downtown and they were updating the [planning ordinances] for downtown and one of the guys that was that worked at the Center City Development Corporation was this guy Gary Papers, who came from Portland.

So he gave me a little background on how the form based zoning was intended to work back in the day, and what the Planning Department wanted. They would go into an area and make a little node. You know on Hawthorne there are these nodes, like every five blocks or something where anything goes. You know, no FAR, no parking…

“I want to set the bar pretty high so that the neighbors - whoever gets to build next to me - no one does a crappy job. They’re going to build something nice, or they’re going to rent for less than my project.”

Height limit up here, something crazy, you know, something crazy like that, and the first project that we get built in that area, the idea was that the Planning Department would be really strict, but have a lot of coordination with the developer to make sure the project was built well, and to a high standard because it would raise the bar for all the other neighbors’ different projects that would come along and they’d build stuff, and as there were more projects, eventually they would form some sort of Business Improvement District. Then the people in the neighborhood would have power and control over what got built next. But the first project is the one that sets the bar.

Maybe things started to move too fast at this point because things are getting built everywhere, but I took that to heart when we did the Creston project and said we've got the zoning on a couple other blocks, and I want to set the bar pretty high so that the neighbors - whoever gets to build next to me - no one does a crappy job. They’re going to build something nice, or they’re going to rent for less than my project.

PDX: So it sounds like you have a lot of good things to say about the CN1 zone and the kind of work that you can do there. Basically, you were scouting for CN1 sites, and this is the one that appeared?

LR: A couple of commercial zones that would work but Andy lives over by Reed College, and he says hey, there's a dedicated bike path, and the they're gonna extend the train over there. We just thought it was kind of a nice and appropriate project. I mean we looked at a whole bunch of stuff as well, but you can only do one project at a time. We're not a big corporation.

PDX: Let's talk a little bit more about the financing of this project. We would love to understand how it the deal was structured, if you had a difficult time with banks, etc. Where were you able to find financing?

LR: It was mostly… there was just funny that there were a couple local banks that wouldn’t touch us because there was no parking, more than anything else.

But the deal is I have a very simple partnership or I try not to have preferred returns for investors because that kind of puts the investors and developers at odds, and I try to just say, hey, everyone's in it together. I try to also to leverage my architecture fee and sweat equity so that sometimes takes a bank… it has to kind of think about that for a little bit, and try to find a good group of people that want to hold onto a building as opposed to trying to have it be speculative, and sell a building or have some crazy structure to their returns. I want people that are in for that for the long haul, that's all.

PDX: Well with all that being said all the challenges that come with designing and constructing anything new, what were some of the things that might have made the project easier to execute in the first place?

LR: After I did the three buildings I swore never to do three buildings again because it's an inordinate amount of exterior wall and then it got me nuts as an architect, as I'm trying to design so many elevations. That was more challenge than I thought, so the reality of it was really simple in plan; I've got three buildings clustered around a tree. It's the transition green into the neighborhood. But then it was like twelve elevations, and I hate doing elevations! I totally like figuring out 50 units in section and all sorts of other stuff.

Next building, I don't care what it is. It's gonna be one. I'm not gonna do a campus of buildings again because that was a challenge. But it was kind of fun too, so I don't know…

PDX: What drove you into the direction of doing three separate buildings, a campus…

LR: It was a low infrastructure building, and just being able to occupy and activate the whole site, you know that was part of it, we've done a similar project in San Diego where it was an entire city block, designed by five different architects everyone did their own building. It was just it was really fun at that scale.

PDX: Do you have any plans of doing more projects in Portland in the future?

LR: Yeah, yeah, we're doing a little project in Brooklyn, on Milwaukie. It's across the street from Andy’s office; another eighteen unit project. It's different, it's a narrow and deep lot so the building is kind of like a long bar, But there's a little twist to it, you know.

PDX: Has it already been submitted for review is there something that we could go and look?

LR: It’s under construction. And you should talk to Andy. He’s my lead partner he's got his office across the street. We've known each other since the mid 90’s. We've talked about doing projects the whole time, so this will be our second one together. Our experience is so deep that we have an elevated level of conversation, and to me it's endearing because it's like he's a general contractor, and we can talk to urbanism.

The way it was developed was great at that area at the time. It was it was blighted and, one of the problems with blight and nobody can get financing ‘cuz there's no comps And this is a way for the city to provide to provide a bunch of housing types that other people could get comps to and get financing

PDX: That's terrific

LR: And actually, then I'll say that about that in Creston, That was the challenge was trying to get comps for the project because there wasn't much new product at that time and so it was hard for them to get comps for one bedroom units I’ve got a lot of one bedroom units and studios. Most of the rental stuff was two bedroom units and the more more efficient stuff in studios and one bedrooms and the housing stock was so old that the rents wouldn't support new construction. We were trying to tell the bank and the appraiser ‘till; we’re blue in the face that no, no we know this is gonna rent for X, and they're like yeah, we don’t believe you, but the appraisal came back, and it said so.

Now today, Portland's had such a boom that there's so many buildings and units it's easier to get in front of comps and get your financing in order. So we were kind of pioneers at that point with that project.

PDX: With that being said do you do you have any plans of doing more projects in Portland in the future?

LR: Yeah, we're doing a little project, in Brooklyn, on SE Milwaukie down there. It's across the street from [Andy’s] office; another eighteen unit project, but it's different, in that it's a narrow and deep lot, so the building is kind of like a long bar. But there's some little twist to it, you know.